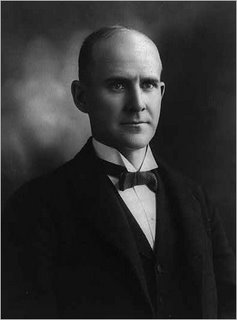

Eugene V. Debs

Written: February, 1898

First Published: The New Time, February, 1898

The century now closing is luminous with great achievements. In every department of human endeavor marvelous progress has been made. By the magic of the machine which sprang from the inventive genius of man, wealth has been created in fabulous abundance. But, alas, this wealth has been created in fabulous abundance. But, alas, this wealth, instead of blessing the race, has been the means of enslaving it. The few have come in possession of all, and the many have been reduced to the extremity of living by permission.

A few have had the courage to protest. To silence these so that the dead-level of slavery could be maintained has been the demand and command of capital-brown power. Press and pulpit responded with alacrity. All the forces of society were directed against these pioneers of industrial liberty, these brave defenders of oppressed humanity—and against them the crime of the century has been committed.

Albert R. Parsons, August Spies, George Engel, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg, Samuel Fielden, Michael Schwab and Oscar Neebe paid the cruel penalty in prison cell and on the gallows.

They were the first martyrs in the cause of industrial freedom, and one of the supreme duties of our civilization, if indeed we may boast of having been redeemed from savagery, is to rescue their names from calumny and do justice to their memory.

The crime with which these men were charged was never proven against them. The trial which resulted in their conviction was not only a disgrace to all judicial procedure but a foul, black, indelible and damning stigma upon the nation.

It was a trial organized and conducted to convict—a conspiracy to murder innocent men, and hence had not one redeeming feature.

It was a plot, satanic in all its conception, to wreak vengeance upon defenseless men, who, not being found guilty of the crime charged in the indictment, were found guilty of exercising the inalienable right of free speech in the interest of the toiling and groaning masses, and thus they became the first martyrs to a cause which, fertilized by their blood, has grown in strength and sweep and influence from the day they yielded up their lives and liberty in its defense.

As the years go by and the history of that infamous trial is read and considered by men of thought, who are capable of wrenching themselves from the grasp of prejudice and giving reason its rightful supremacy, the stronger the conviction becomes that the present generation of workingmen should erect an enduring memorial to the men who had the courage to denounce and oppose wage-slavery and seek for methods of emancipation.

The vision of the judicially murdered men was prescient. They saw the dark and hideous shadow of coming events. They spoke words of warning, not too soon, not too emphatic, not too trumpettoned—for even in 1886, when the Haymarket meetings were held, the capitalist grasp was upon the throats of workingmen and its fetters were upon their limbs.

There was even then idleness, poverty, squalor, the rattling of skeleton bones, the sunken eye, the pallor, the living death of famine, the crushing and the grinding of the relentless mills of the plutocracy, which more rapidly than the mills of the gods grind their victims to dust.

The men who went to their death upon the verdict of a jury, I have said, were judicially murdered—not only because the jury was packed for the express purpose of finding them guilty, not only because the crime for which they suffered was never proven against them, not only because the judge before whom they were arraigned was unjust and bloodthirsty, but because they had declared in the exercise of free speech that men who subjected their fellowmen to conditions often worse than death were unfit to live.

In all lands and in all ages where the victims of injustice have bowed their bodies to the earth, bearing grievous burdens laid upon them by cruel taskmasters, and have lifted their eyes starward in the hope of finding some orb whose light inspired hope, ten million times the anathema has been uttered and will be uttered until a day shall dawn upon the world when the emancipation of those who toil is achieved by the brave, self-sacrificing few who, like the Chicago martyrs, have the courage of crusaders and the spirit of iconoclasts and dare champion the cause of the oppressed and demand in the name of an avenging God and of an outraged Humanity that infernalism shall be eliminated from our civilization.

And as the struggle for justice proceeds and the battlefields are covered with the slain, as Mother Earth drinks their blood, the stones are given tongues with which to denounce man’s inhumanity to man—aye, to women and cellar, arraign our civilization, our religion and our judiciary—whose wailings and lamentations, hushing to silence every sound the Creator designed to make the world a paradise of harmonies, transform it into an inferno where the demons of greed plot and scheme to consign their victims to lower depths of degradation and despair.

The men who were judicially murdered in Chicago in 1887, in the name of the great State of Illinois, were the avant couriers of a better day. They were called anarchists, but at their trial it was not proven that they had committed any crime or violated any law. They had protested against unjust laws and their brutal administration. They stood between oppressor and oppressed, and they dared, in a free (?) country, to exercise the divine right of free speech; and the records of their trial, as if written with an “iron pen and lead in the rock forever,” proclaim the truth of the declaration.

I would rescue their names from slander. The slanderers of the dead are the oppressors of the living. I would, if I could, restore them to their rightful positions as evangelists, the proclaimers of good news to their fellowmen—crusaders, to rescue the sacred shrines of justice from the profanations of the capitalistic defilers who have made them more repulsive than Augean stables. Aye, I would take them, if I could, from peaceful slumber in their martyr graves—I would place joint to joint in their dislocated necks—I would make the halter the symbol of redemption—I would restore the flesh to their skeleton bones—their eyes should again flash defiance to the enemies of humanity, and their tongues, again, more eloquent than all the heroes of oratory, should speak the truth to a gainsaying world. Alas, this cannot be done—but something can be done. The stigma fixed upon their names by an outrageous trial can be forever obliterated and their fame be made to shine with resplendent glory on the pages of history.

Until the time shall come, as come it will, when the parks of Chicago shall be adorned with their statues, and with holy acclaim, men, women and children, pointing to these monuments as testimonial of gratitude, shall honor the men who dared to be true to humanity and paid the penalty of their heroism with their lives, the preliminary work of setting forth their virtues devolves upon those who are capable of gratitude to men who suffered death that they might live.

They were the men who, like Al-Hassen, the minstrel of the king, went forth to find themes of mirth and joy with which to gladden the ears of his master, but returned disappointed, and, instead of themes to awaken the gladness and joyous echoes, found scenes which dried all the fountains of joy. Touching his golden harp, Al-Hassen sang to the king as Parsons, Spies, Engels, Fielden, Fischer, Lingg, Schwab and Neebe proclaimed to the people:

“O king, at thyCommand I went into the world of men;

I sought full earnestly the thing which I

Might weave into the gay and lightsome song.

I found it, king; ’twas there. Had I the art

To look but on the fair outside, I nothing

Else had found. That art not mine, I saw what

Lay beneath. And seeing thus I could not sing;

For there, in dens more vile than wolf or jackal

Ever sought, were herded, stifling, foul, the

Writhing, crawling masses of mankind.

Man!Ground down beneath oppression’s iron heel,

Till God in him was crushed and driven back,

And only that which with the brute he shares

Finds room to upward grow.”

Such pictures of horror our martyrs saw in Chicago, as others have seen them in all the great centers of population in the country. But, like the noble minstrel, they proceeded to recite their discoveries and with him moaned:

“And in this worldI saw how womanhood’s fair flower had

Such pictures of horror our martyrs saw in Chicago, as others have seen them in all the great centers of population in the country. But, like the noble minstrel, they proceeded to recite their discoveries and with him moaned:

“And in this worldI saw how womanhood’s fair flower had

Never space its petals to unfold.

HowChildhood’s tender bud was crushed and trampled

Down in mire and filth too evil, foul, for beasts

To be partaken in. For gold I saw

The virgin sold, and motherhood was made

A mock and score.

I saw the fruit of labor

I saw the fruit of labor

Torn away from him who toiled, to further

Swell the bursting coffers of the rich, while

Babes and mothers pined and died of want.

I saw dishonor and injustice thrive. I saw

The wicked, ignorant, greedy, and unclean,

By means of bribes and baseness, raised to seats

Of power, from whence with lashes pitiless

And keen, they scourged the hungry, naked throng

Whom first they robbed and then enslaved.”

Such were the scenes that the Chicago martyrs had witnessed and which may still be seen, and for reciting them and protesting against them they were judicially murdered.

Such were the scenes that the Chicago martyrs had witnessed and which may still be seen, and for reciting them and protesting against them they were judicially murdered.

It was not strange that the hearts of the martyrs “grew into one with the great moaning, throbbing heart” of the oppressed; not strange that the nerves of the martyrs grew “tense and quivering with the throes of mortal pain”; not strange that they should pity and plead and protest. The strange part of it is that in our high-noon of civilization a damnable judicial conspiracy should have been concocted to murder them under the forms of law.

That such is the truth of history, no honest man will attempt to deny; hence the demand, growing more pronounced every day, to snatch the names of these martyred evangelists of labor emanicapation from dishonor and add them to the roll of the most illustrious dead of the nation.

Courtesy of Marxist Internet Archives

No comments:

Post a Comment