Owen Hsieh

The Town of N by Leonid Dobychin is a novella about a nameless boy in

provincial, pre-revolutionary Latvia. Beginning in 1901 when he is seven years

old and concluding a decade later. It has been compared to James Joyce’s Ulysses,

there is hardly a plot, chronological in style, it is replete with 100

different characters over 102 pages. Something of a minor epic, it has a number

of thematic threads. It delights with a litany of understated literary

references from the naive perspective of the young boy while creating a

compelling portrait of what parochial, pre-Soviet, provincial life.

While chronicling the major events in the first quarter of the

20th century with the introduction of rubber tyres, the electric light, the

gramophone and living pictures, the disastrous Russia-Japan war, and the failed

revolution of 1905, this allegory sparkles with literary metaphor.

The town of N is a reference to Nikolai Gogol novel Dead Souls,

which is set in a town of the same name. Some of the characters are smug,

bigoted and mean, Gogol’s characters seem to reappear! For instance we see

another instance of a Chichikov the con man, the insipid Manilov, the

misanthropic Sobakevich, the miser Plyushkin, and the untruthful Nozydrov. It

also contains references to the works of Cervantes, Chekhov, Dostoyevsky,

Pushkin, Tolstoy and Dickens.

Innovative, playful, ironic and inventive, rich in symbolism. Each

reading delights with a series of new discoveries. Minor details that are

seemingly hardly worth examining on the first reading wait to be discovered and

rediscovered on the next read through. This is a good example of the novel that

the serious critic would aim to read once per year, re reading it anew with

fresh eyes and (ideally) a greater appreciation for the nuance with the

historical and literary references.

The Translator, Richard Chandler Borden, explains Dobychin’s

method in his introduction to the novella:

“Dobychin’s texts demand close reading and rereading. Much

information necessary for appreciating their subtleties is revealed

sequentially and inexplicitly.”

“[He] was an excruciatingly, slow writer, who would spend days

even months on the tiniest of details, often producing stories of but four or

five pages in length and expressing astonishment, perhaps disingenuously, that

others could churn out so many works of dimensions attractive to publishers.

The result of such laborious creation is that the reader may invest fully in

each detail - each word, each oddity of syntax, diction, or style - confident

it has been selected for its maximum informativeness. Nothing has been left to

chance.”

This book is a joy to read, a full appreciation of all the

subtleties of this novel hardly seems possible in this short review. This is a

work of genius by a modernist master.

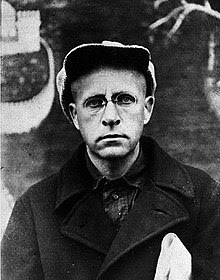

But sadly, the appearance of his novel preempted vitriolic

denunciation in the ensuing year that led ultimately to the authors

suicide.

“Dobychin's experimentalism was not understood by his

contemporaries, as it adhered neither to the dictates of socialist realism nor

imitated the ornamental prose of Pilniak and Zamiatin, and he remained on the

periphery of Russian literary life."

(Cornwell and Christian (eds.), Reference Guide to Russian

Literature, 1998, p. 53).

After the replacement of the various artistic schools and unions

with the official union of Soviet Writers in 1934, and the adoption of the ‘new

line’ of socialist realism in all the arts at its congress the same year.

Dobychin had the great misfortune of publishing in 1935, a year prior to the

Stalinist campaign against formalism reaching its apotheosis.

Dobychin takes the unenviable title of being probably the last

work of formalism published in this period and was savaged by the Stalinist

literary critics.

Where formalists sought to analyse literatures form, structure and

style rather than its socio-political content. The adherents of Socialist

realism gave primacy to political considerations in literature, aiming to

create works that showed the positive side of Soviet life with a blend of

optimism and patriotism after the policy of socialism in one country. It

discouraged abstraction and experimentation and favoured a conventional

straightforward narrative structure. The Town of N was an

anathema to the socialist realists.

“Socialist realism was a special theory worked out for the sphere

of art, establishing a sort of normative aesthetic code, which could not be

deviated from without incurring penalties.” - (Boris Kagarlitsky - The Thinking

Reed, 1989, pp 112).

Dobychin was singled out in 1936 as the first whipping boy and

chief formalist. With unsubtle hints that he was a class enemy and accused of

sharing the views of the novels protagonist:

After a fierce meeting with the writers union on March 25th,

1936:

“He responded only by stating that, regrettably, he could not agree with what had been said and departed. He disappeared the next day, after organising his affairs and confiding plans to kill himself to an acquaintance, he later proved to have been a police spy assigned to report on his activities. He was never seen again.”

His body was fished out of the Neva river months later, a presumed

suicide.

It is a tragedy that Dobychin joins the ranks of Bulgakov, Babel,

and a generation of Russian Avante Garde authors who were born from the

creative impulse created by the Bolshevik Revolution, with the democratization

of the arts and the ensuing flourishing and healthy competition of the artistic

schools of thought but were later repressed or silenced under Stalinism.

Dobychin’s life was cut untimely short, and all we have of his literary legacy

is a collection of short stories entitled: Encounters with Lisa and

other stories, and this novella.

It is worth quoting Trotsky and Rogovin at length to give the

concluding comments to highlight the opposing perspective of the left

opposition against the philistinism of the Socialist realists:

“While the dictatorship had a seething mass-basis and a prospect

of world revolution, it had no fear of experiments, searchings, the struggle of

schools, for it understood that only in this way could a new cultural epoch be

prepared. The popular masses were still quivering in every fiber, and were

thinking aloud for the first time in a thousand years. All the best youthful

forces of art were touched to the quick. During those first years, rich in hope

and daring, there were created not only the most complete models of socialist

legislation, but also the best productions of revolutionary literature. To the

same times belong, it is worth remarking, the creation of those excellent

Soviet films which, in spite of a poverty of technical means, caught the imagination

of the whole world with the freshness and vigor of their approach to reality.”

“In the process of struggle against the party Opposition, the

literary schools were strangled one after the other.”

“The bureaucracy superstitiously fears whatever does not serve it

directly, as well as whatever it does not understand”

“The struggle of tendencies and schools has been replaced by

interpretation of the will of the leaders. There has been created for all

groups a general compulsory organization, a kind of concentration camp of

artistic literature. Mediocre but “right-thinking” storytellers like

Serafimovich or Gladkov are inaugurated as classics. Gifted writers who cannot

do sufficient violence to themselves are pursued by a pack of instructors armed

with shamelessness and dozens of quotations. The most eminent artists either

commit suicide, or find their material in the remote past, or become silent.

Honest and talented books appear as though accidentally, bursting out from

somewhere under the counter, and have the character of artistic contraband.”

“The life of Soviet art is a kind of martyrology.” - (Trotsky, the

Revolution Betrayed, 1937, pp 153-156).

and:

“There is no place for talented people on Soviet soil, that party

policy in the realm of art excludes creative experimentation, the independence

of the artist, and the display of genuine mastery.” He associated the

possibility that Soviet culture might flourish with the establishment of a

democratic regime in the land, based on the political views which the

Trotskyist have been defending”. - Isaac Babel in conversation with Eisenstein

(Stalin’s Terror of 1937-1938: Political Genocide in the USSR, Vadim Z Rogovin,

1997, pp 227)